Greening the Campus

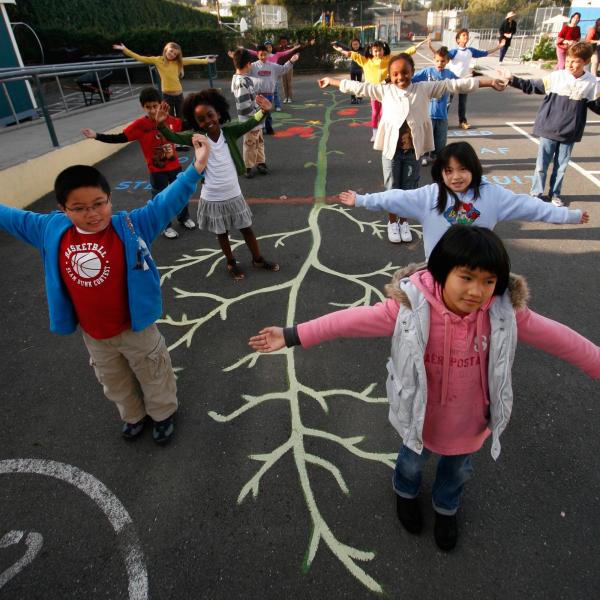

Learning about sustainability comes alive on a campus that is designed and operated with imagination.

The school demonstrates its respect for the environment and its stewardship of resources. The campus serves as a laboratory for exploring solutions to environmental issues and a model of sustainable practice. It becomes an inspiration and model for the surrounding community and to other institutions. Students and staff are healthier and more productive on campuses that are good for the environment.

Campus Design and Construction

The Collaborative for High Performance Schools summarizes the major features of a "high-performance" campus:

- Healthy

- Comfortable

- Energy Efficient

- Material Efficient

- Easy to Maintain and Operate

- Commissioned (a process for monitoring the efficiency of building systems during design and construction)

- Environmentally Responsive Site

- A Building That Teaches

- Safe and Secure

- Community Resource

- Stimulating Architecture

- Adaptable to Changing Needs

CHPS and the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) for Schools program of the U.S. Green Building Council provide resources and certify the greenness of major construction and renovation programs. Consult their websites for detailed checklists and manuals that describe specific practices that protect the environment, reduce operating costs, and enhance teaching and learning.

Getting Toxins Off Campus

Harmful products such as toxic cleaning supplies, pesticides, asbestos, and volatile organic compounds off-gassed by paints and carpets make their way into the water, air, and food web on which plants and animals depend. They can also pose significant threats to the health of students and staff (of the forty-eight pesticides used most commonly in schools, the EPA classifies twenty-two as possible or probable carcinogens).

Administrators and parents for whom "sustainability" seems an abstraction will often respond when the health of students and staff is at stake.

Less dangerous alternatives to toxic products exist, including systemic solutions such as integrated pest management, as practiced by the Los Angeles Unified School District and elsewhere. A number of excellent organizations have developed guidelines, policies, and recommendations for green cleaning and healthier campus maintenance. See for example the Green Schools Initiative and the Healthy Schools Network.

Environmentally Preferable Purchasing

Every school buys office and school supplies, cleaners, pesticides, fertilizers, food, playground equipment, and vehicles. The billions of dollars spent and the millions of tons of materials that pass through schools provide opportunities for acting sustainably and teaching by example.

The EPA defines "environmentally preferable" as “products or services that have a lesser or reduced effect on human health and the environment when compared with competing products or services that serve the same purpose.” The enormous collective purchasing power of schools can also create markets for products that benefit the environment, create jobs, and raise the quality of life of communities.

Products are rarely completely virtuous or completely undesirable. Some questions to ask when considering a purchase:

- What are the environmental and social impacts over the lifetime of the product or service?

- Is the product reusable or more durable?

- Is there an available product with recycled content that performs just as well?

- Does it conserve energy or water?

- Is it less hazardous than alternatives?

- What happens at the end of its life? Can it be recycled?

- Will the manufacturer take the product back? Will it need special disposal?

- Is a similar product grown or produced locally?

- Under what conditions is it grown, extracted, or manufactured? Are the people who produced it fairly compensated?

As environmentally preferable purchasing becomes more prevalent, resources proliferate. The Green Schools Initiative’s “Green Schools Buying Guide" contains information on a wide range of products, buying tips, and sample policies. Organizations such as the Green Purchasing Cooperative Program at Rutgers University offer advice to K–12 schools or permit schools to purchase through them

Waste Reduction

The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that within five years, one-third of all landfills in the nation will reach capacity. California schools alone collectively dispose of more than 750,000 tons of waste yearly, of which nearly half is paper and another quarter organic material.

A campus trash audit is an eye-opening exercise that offers students immediate feedback about the school’s contribution to its community’s waste stream, and provides a baseline for redesigning the school’s waste management system.

Recycling is an obvious response, while remembering that the sustainability theme song is still "Reduce, Reuse, Recycle" in that order. Simple steps make a difference in the success of recycling programs. (Labeling trash bins "landfill" reminds everyone that nothing is thrown "away." People are more likely to recycle when recycling containers are placed next to landfill receptacles than when they're in separate locations.)

Sustainability Audits

A sustainability audit by students and staff can serve as a tool for planning, goal setting, and measuring progress. It's also an opportunity to learn how sustainability issues arise in day-to-day decisions. It's a chance to deliberate about responses that will have the largest impacts. For an example of a particularly thorough audit, see Northfield Mount Hermon School in Massachusetts.

Paying for Campus Greening

In a tough economy, schools need creative funding strategies for building, renovating, and retrofitting.

The easiest way to "raise" money is not to need it. The Department of Energy estimates that simple technological and behavioral changes — such as turning off computers, copiers, and lights when not in use — can reduce energy use by as much as 33 percent.

Some schools have found that campus greening can actually be a fundraising tool, enabling them to tap alums who have not given previously.

For examples of other founding sources and successful strategies see the "Guide to Financing EnergySmart Schools" from the Department of Energy or the Green Schools Initiative's "Greenbacks for Green Schools."

Besides such expected government sources as the Department of Energy, schools have tapped funds such as the Homeland Security Grant Program, by designating buildings for use by the public in case of a disaster. North Carolina State University maintains an extensive database of government and utility grants and incentives.

Through power-purchase agreements, schools have partnered with private firms that can take advantage of tax credits that schools cannot. The independent company pays the upfront costs to install, say, a photovoltaic system. It receives a tax break. Then it sells energy generated by the new system to the school at a rate lower than the local utility’s. The school converts to solar energy without an initial outlay and reduces energy costs as well.

School districts have negotiated performance contracts, for instance with HVAC manufacturers. The companies guarantee a certain level of energy savings, allowing the district to take out a loan or sell bonds to be repaid from the savings.

Shifts in perspective that characterize systems thinking can help persuade cost-conscious trustees or school boards. One shift is from minimizing first costs to optimizing life-cycle costs — from focusing on getting the building up and the kids through the doors to weighing the long-term expenses of operations, insurance, maintenance, and future replacement of worn-out equipment and structures.

A second shift is to integrated design. This whole systems approach brings the client and the architects, contractors, and specialists (electrical, structural, and mechanical engineers, for example) into the design process as early as possible. By collaborating and treating the project and its parts as an interconnected system, integrated design optimizes efficiency, cost, and the building’s effect on teachers and students.

A third shift is to consider the total costs and benefits to the wider community. A much-quoted 2006 study, "Greening America’s Schools: Costs and Benefits," dramatically concluded that green schools cost on average less than 2 percent more than conventional schools to build, but provide financial benefits twenty times as large. (Greg Kats, "Green School Design: Cost-Effective, Healthy, and Better for Education.")

The largest estimated payoffs come from projecting earnings by graduates who would learn more, score higher on tests, and get better jobs. Just the energy and water savings are more than three times the expenditure for building green. The school or district benefits from better student attendance, fewer teacher sick days, and less staff turnover. Other benefits accrue to the community, including lower health care, reduced demand on water systems, higher tax revenues, reduced social inequity, less air and water pollution, and the creation of green collar jobs.

Adapted from the Center's book Smart by Nature: Schooling for Sustainability (Watershed Media, 2009)..