EcoStars: Enabling Students to Become Environmental Stewards

Guided by our school vision "Mary E. Silveira School is a place where children want to be," our school community has produced a program called EcoStars.

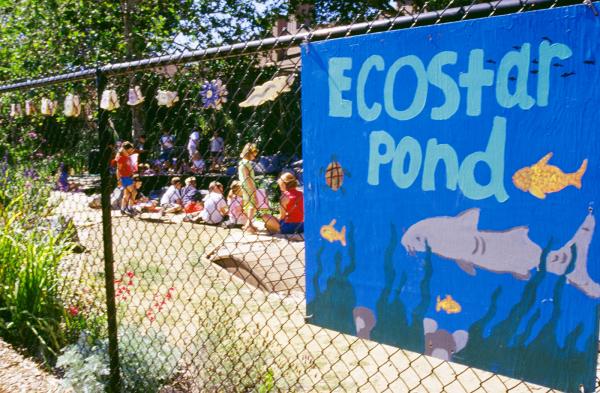

The program comprises children, staff, and parents working together to transform areas of the school grounds into educational resources or outdoor classrooms. The aim is to move beyond simply beautifying the grounds towards using the school grounds as an educational tool for students. Creating a sense of place and community and enabling the community to become stewards of the site is the central premise of EcoStars. Examples of EcoStar projects include expanding the school garden, planting a butterfly garden, designing a composting system for the café and garden, erecting a garden shed, writing a guide for and reforesting nearby Blackstone Canyon, building a pond habitat on a section of the school grounds, restoring creeks through the STRAW Project, and implementing a schoolwide recycling program.

EcoStars began in our School Site Council (a body of parents and educators who oversee the School Improvement Plan and budget). The program's goals are:

- To teach and practice the principles of ecology

- To heighten children's environmental awareness and promote stewardship

- To integrate subject matter areas such as science, math, and social studies

- To instill in students a sense of ownership, pride, and responsibility

- To collaborate with and garner support from community partners (such as Master Gardeners, Bay Model, California Department of Fish and Game, Marin Conservation Corps, and the Center for Ecoliteracy)

Ecostars projects involve children from Day One. They take part in the designing, planning, implementation, and maintenance of their school environment. In this way, the schoolyard becomes an extension of the classroom. For example, four years ago two red-eared slider turtles joined our school community. They had outgrown their tank and students wanted to create a more natural habitat for the turtles. Students generated a list of questions they would need to answer before they could begin to make the pond. They met with consultants and S.E.E.D. parents (School Environmental Education Docents) to find out how deep the pond would have to be, what kind of plants they would need, what kind of security issues were involved. With basic information in hand, students mapped the site and made a 3-D model of the pond.

When they were ready to begin construction, parents in the construction business and an engineer at the San Francisco Bay Model joined the team. Working together they began building the pond. Once the filtration system was in place, the Marin/Sonoma Mosquito Abatement officer taught the group about mosquito control. Next, students contacted a fishery biologist from the California Department of Fish and Game to find out what other kinds of wildlife they could introduce into the pond. Brimming with knowledge gained from this project work, students are writing a pond guide to record the plant and animal life in this schoolyard habitat. The guide also will include a section that tells how to maintain the pond.

Building a pond was part of our vision to show students that science is all around us. Research has shown us time and again that children learn best by doing. In creating and maintaining a pond, our students participate in real-life science. This is a site-based, hands-on, solutions-oriented approach to environmental education that teaches ecological literacy as well as team building, critical thinking, and problem solving in a real-world setting. This process allows students to experience ecology first hand. For example, in building their pond, students developed an understanding of the numerous ways that design interconnects natural systems and the built environment. EPBL projects, like creating a pond habitat, help students gain an understanding of ways in which their daily decisions affect the well being of the places they inhabit.

From the beginning, the pond project has generated questions that students have had to deal with over the years. For example:

- How will the pond drain when it rains?

- What kind of food does a sturgeon need?

- Will the turtles eat the mosquito fish?

- Did the great blue heron eat some fish — he stayed three hours? Does it matter?

- Why did the turtle die?

- How can we keep the leaves from clogging up the drain?

As a result of dealing with questions like these, students learn to be conscious designers of their habitat and stewards of their place.

Programs like EcoStars are difficult to manage and maintain. They are not part of the school budget, so there are grants to be written and donations to be solicited. In the beginning, the School Site Council managed EcoStars and worked with parent volunteers. Now, thanks to a grant from the Center for Ecoliteracy, EcoStars has a coordinator who helps teachers and students with training, questions, research, and meets with me every week.

In spite of this support, with current state mandates, teachers often feel overwhelmed with curriculum requirements. For this reason, outdoor learning can seem like an additional burden. To address these concerns, we outline how a project will help meet learning standards and curriculum requirements for all subject areas.

Is there a better way to study the life cycles and interconnections than for students to watch monarch butterflies emerging on milkweed plants that they have planted? Is there a better way to learn measurement than to map the garden area on the school grounds? Is there a better place for journal writing or sketching than a natural area that students have helped to create? We don't think so.