School Food in Clovis, California is Tasty, Diverse, and Entertaining

Ask Clovis (California) Unified School District’s food service director Robert Schram what drives his menu, and he doesn't miss a beat. "The students," he says. "It's all about what they want." But instead of pepperoni pizza and french fries, think fragrant pho soup and kung pao quesadillas — healthy, hearty, and creative dishes with an ethnic twist. "We're winning if students find comfort in something that tastes close to home."

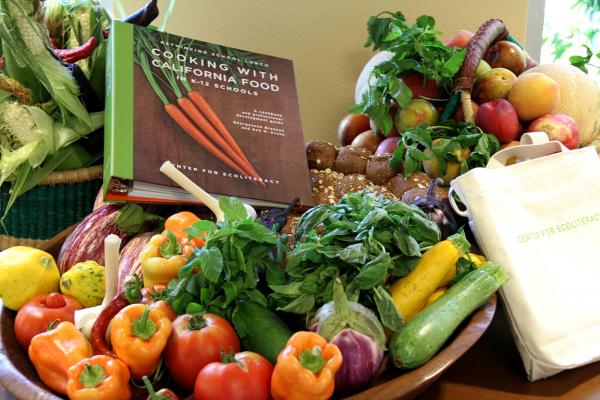

Faced with the herculean task of feeding 25,000 finicky schoolchildren a day, Schram is always on the lookout for innovative ideas. Last summer, he traveled to Davis, California for the Center for Ecoliteracy's statewide conference and cooking school for leaders in school food service reform. There he discovered the Center's new cookbook and professional development guide, Cooking with California Food in K–12 Schools. It introduces the dynamic 6-5-4 School Lunch Matrix — a new concept based on six dishes students already know and love (salads, soups, pastas, rice bowls, wraps, pizza toppings); five ethnic flavor profiles (African, Asian, European/Mediterranean, Latin American, Middle Eastern/Indian); and four seasons.

"The cookbook is just phenomenal," Schram enthuses. "It inspires me to think of food in many different ways. Let's talk about the six dishes. We make jambalaya as a rice bowl dish, but I could also make it into a wrap. The five flavors can also be commingled. Spaghetti can be served as spaghetti (pasta) or the popular spaghetti taco (a form of wrap). And all groups can be changed by the four seasons. This helps create a menu that's entertaining, movable, and alive."

School food transformation has been an ongoing process for Clovis Unified, which is gradually moving toward more scratch cooking, despite labor and facility challenges. It now makes 90 percent of its bread in-house with whole grain flour, refrains from frying any foods, and bans the sale of sodas or "regular" chips during the school day on all of its campuses. While salad bars are not yet available, fresh fruits and vegetables are almost always integrated into meals. Schram credits the Center's cookbook with reminding him about the importance of seasonality in cultivating the "true flavors" of food. Located in the midst of the agriculturally rich San Joaquin Valley, Clovis Unified recently began working with farmers to get more local, seasonal produce into the kitchens and onto the menus. Schram also encourages Clovis East High School, which he describes as the district's "agriculture school," to supply the cafeterias with homegrown fruits and vegetables. "It's a big selling point for the students," notes Schram. "They get pretty jazzed: 'Wow, the kids we know are growing this stuff!'"

Schram is particularly sensitive to the demographics of the student population he serves: 36 percent are Hispanic or Latino, and many other ethnicities are represented, including African American, Hmong, Filipino, and American Indian. "The 6-5-4 Matrix really makes you step back and think about how we can address all of our different ethnicities through food and find ingredients that blend cultures to make 'fusion foods,'" he says. "We take foods to areas where success seems likely, but a lot of foods transcend culture, so ethnicity doesn't always matter so much. For example, jalapeños and onions align with both Thai and Spanish cuisine. Creole is spicy hot, so it's not such a stretch to imagine that it would appeal to other populations. It's amazing what dishes can be created with the cookbook's vegetable and spice lists alone, using a wide variety of flavor profiles."

The cookbook also put "old" ingredients in a new light. "I never thought of peanuts as part of the African diet. I thought they were more Thai or American," he muses. "You start asking questions and getting excited because the target markets are there. In the melting pot of California, I could eat any one of these cuisines on a given night. And culturally, these kids know a lot about each other's foods. Asian populations are especially attuned to this."

While Schram and his team have used specific recipes from the cookbook (including the Coconut Mandarin Soup and the Tabbouleh), they like to mix things up and experiment on their own — a process always guided by student feedback. Schram spends most of his time traveling to the district's 47 schools, where he chats directly with students in the lunchroom and offers taste tests. "You always have to show them that you're sincerely concerned about their well-being. I ask them what they like and dislike, what they want and don't want. I tell them about a new dish in advance and plant a seed so they look forward to it."

In fact, the idea of pho on the menu came from a group of students who told Schram that they had never eaten at school because "cafeteria food sucks." "I could’ve gotten offended, but you really have to listen to kids, and sometimes you have to dig. I asked, 'What would it take to make you come eat here?' They all laughed, and one of them said, 'Pho soup.'" After trying the dish for the first time at a restaurant and conducting research, Schram concocted his own version in the Clovis West High School kitchen. "The aroma was just bellowing throughout the campus," he recalls. "We gave 4-ounce sample cups to the students. One kid came running up and said, 'Dude, where’s the pho?' To this day, it's still going strong at Clovis West and East."

For his efforts to create a healthy, student-driven menu, the California Endowment named Schram one of six inaugural "Health Happens Heroes" in October 2011. These awards honoring school "nutrition innovators" reflect the state's growing commitment to food reform. In 2010, for example, the California Department of Education (CDE) selected four nutrition services directors from different districts to serve as "Ambassadors" to other colleagues, with the goal of training 200 child nutrition leaders on new USDA and White House initiatives. At CDE's conferences around the state, Cooking with California Food was presented to all participants as a go-to resource. At one of them, Ambassador Pilar Gray, nutrition services director for Fort Bragg Unified, created two of the cookbook's recipes (Broccoli-Raisin-Walnut Salad and Curried Chicken Salad Pita) for attendees to sample. "My staff found the recipes easy to prepare, and everyone really seemed to enjoy them," she says. "We hope to introduce them into our school meals in the near future."

For his part, Schram is using the cookbook in professional development trainings for his own staff and working with them to implement its 6-5-4 strategy. "We're really trying to tap into the resources of our people to help them mold what we're feeding the population. No one knows what the students want to eat better than the people who deal directly with them," he notes. "The cookbook talks about what students really want to eat. When they buy in to a dish, it becomes theirs. They're a spokesperson and customer for life."